Flt Lt Arnold George Christensen

(1922 - 1944)

Profile

Arnold George Christensen was born Danish in New Zealand. He enlisted in the Royal New Zealand Air Force in 1940 and was trained as pilot. Shot down on his first operation over Dieppe, he was imprisoned in Stalag Luft III. He was one of the fifty prisoners executed by the Gestapo following the Great Escape on 23/24 March 1944.

Arnold George Christensen was born on 8 April 1922 in Hastings, Hawkes Bay, New Zealand.[1] Christensen’s father was Danish. Anton Christensen, was born in Randers in Denmark in 1891,[2] but had emigrated to New Zealand in 1912. Christensen’s father and mother, Lilian Alice Christensen (née Ladbrook), married in 1920.[3] Hence, Christensen was a Danish national from birth. The naturalisation of his father on 6 October 1925[4], and with him the family, meant that Christensen became a British Subject.

Prior to enlistment, Christensen worked as a journalist with the Hawkes Bay Daily Mail newspaper.[5]

Pilot training

Christensen volunteered for the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) in 1940 and trained as pilot.[6] At least part of his flying training was carried out in Canada, where many pilots trained as part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). Christensen attended course No. 42 at 4 SFTS in Saskatoon from 19 November 1941. Following the Wings parade on 27 February 1942.[7] all 39 New Zealanders were posted to 1 “Y” Depot in Halifax for service overseas, i.e. in Europe.[8] He was promoted to Pilot Officer.[9]

Christensen arrived in England in March 1942. He was posted to 41 OTU at RAF Old Sarum, where he was trained in an Army Co-operation role. He was not very enthusiastic about this role. In a letter to his mother in late June 1942 he wrote:

I was far from enthusiastic about coming here, because I have been pushed into an Army Co-operation course, however, now I am here I shall have to make the best of it. The types of ‘plane we will be flying in a very short time are, I understand, still secret, so that’s “tabu;” but in the meantime we are bugging around in Harvards, which they have in New Zealand, having lots of fun trying to find our way round this English countryside [in] complicated navigational exercises.[10]

The secret aircraft, that he was to fly, was the Mustang Ia fighter. On 13 August 1942, Christensen was posted to 26 Squadron at RAF Gatwick.[11] This squadron had converted to the Mustang in January 1942.[12]

Operation Jubilee: the Raid on Dieppe

On 19 August 1942, more than 6,000 forces raided the French coastal town of Dieppe (Operation Jubilee). The operation was the first major joint operation conducted by the British and Commonwealth forces in the European theatre.[13] Nearly 5,000 Canadians, approximately 1,000 British Commandoes and 50 American Rangers was involved in the landring operations. At sea eight Allied destroyers supported the operation, and in the air seventy-four Allied air squadrons provided cover and tactical reconnaissance.[14] A total of forty-seven Army Co-operation Mustangs were involved in the operation. Mustangs from 26 and 239 Sqns at Gatwick were the first reconnaissance machines in the air at 0435 hrs.[15]

The raid provided valuable, but costly lessons for the later invasion of Normandy. Of the nearly 4,961 Canadians embarking on the operation, only 2,210 returned to England, and many of these were wounded. There were 3,367 casualties, which included 1,946 prisoners of war. 916 Canadians lost their lives.[16]

Royal Air Force and Luftwaffe fought a hard battle in the air. At the end of the day, according to the renowned aviation author Norman Franks, the RAF could claim a great victory.[17] Many aircraft had been lost on both sides. On the Allied side, the Army Co-operation had the highest level of casualties per squadron: the four squadrons involved lost ten aircraft. This was due to the deep penetration required of these squadrons bringing them well beyond the Allied fighter cover.[18]

First and Last Operation

During the course of the day, 26 Squadron carried out eleven sorties involving eighteen individual sorties. The sorties were made in the area of Le Havre, Rouen, Abbeville, and the mouth of the Somme river. The coast roads leading to Dieppe, and those from Amiens, Rouen, Yvetot and Le Havre, where reinforcements were expected to come from, were reconnoitred and a continued basis by the squadrons. At 0800 hrs. the squadron sent out two Mustangs on tactical reconnaissance. Plt Off. E. E. O’Farrell took off in AG463, while Christensen took off in AL977. It was Christensens first operational sortie. From Gatwick they flew to the Dieppe area via the Beachy Head route. They made contact with the Command Ship in the Channel, and then proceeded to the area. While flying over the area, both aircraft were struck by flak and small-arms fire. They returned for home, but O’Farrell (108142) went down in the Channel. Christensen struggled to maintain altitude, and in the end he bailed out. He landed in the Channel uninjured, and for two days he remained adrift in the emergency dinghy. He washed ashore on the French coast, where he was soon captured by the Germans. O’Farrell survived as well. Both Christensen and O’Farrell was sent to Stalag Luft III.

Stalag Luft III, Sagan

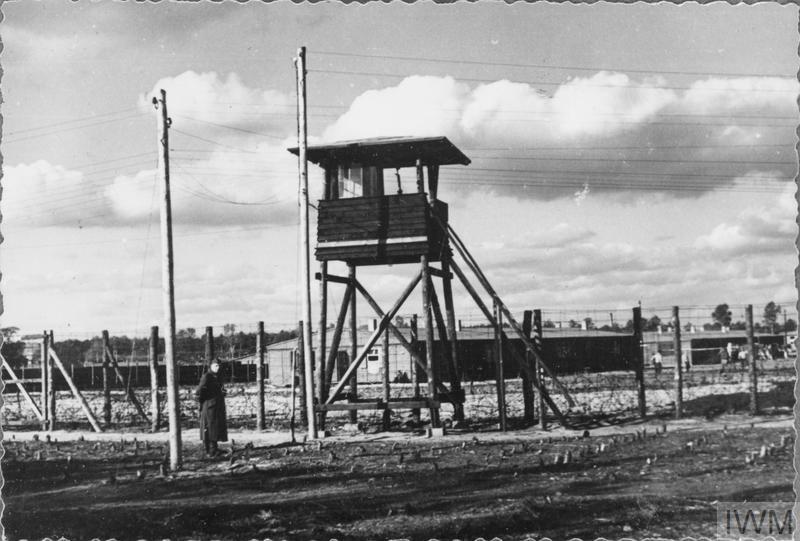

Stalag Luft III—or Stammlager Luft III—was a large prisoner of war camp outside Sagan in Lower Silesia (today Zagan in Poland). The camp was run by Luftwaffe and established for the internment of Allied aircrew. The first part of the camp, the East compound, opened in March 1942, and over the following three years the camp was expanded to hold more than ten thousand prisoners of war. Stalag Luft III made its way into the history books because of two escapes: from the East compound in October 1943 and from the North compound in March 1944. It is not clear, when Christensen arrived in Sagan, but it is most likely, that he was imprisoned in the East compound initially. The North compound opened in late March 1943, and a number of prisoners were transferred from the East compound to the new compound from early April. Christensen was one of them.

Within a few months two Danes had joined Christensen in the camp: Frank Sorensen, who served in the RCAF was shot down over Tunis and arrived in April 1943, and Arne Bøge, serving in the Norwegian air force was captured following a mission over Northern France in August 1943 and was sent to the camp.

Before the end of April 1943, work had begun to construct three tunnels. The tunnels—named “Tom”, “Dick” and “Harry” for security purposes—were part of an ambitious plan to free two hundred prisoners of war from the camp. The plan had been conceived by Sqn Ldr Roger Bushell, codenamed ’Big X’, who chaired the escape committee of the Northern compound. Christensen joined the escape committee’s intelligence section gathering intelligence on Denmark that might prove useful to escapees on the run.[19]

It was no easy task to dig the tunnels. First of all, it was no coincidence that the area outside Sagan had been chosen for the camp. The sandy soil made tunneling difficult and dangerous. Secondly, the Germans had built the huts about a foot above ground, and inspected the the area below for tunnel entrances on a regular basis. The floors of the washrooms and kitchens were made of concrete and the same was the case of the area below the stoves in the corner of each living-room.

In March 1944, the prisoners have been working on “Harry” for nearly a year. In the meantime, the German guards had discovered the entrance of “Tom”, and work on “Dick” was cancelled. It was decided to concentrate work on “Harry”, and by mid-March it was estimated that the tunnel reached from the entrance under the stove in room 23 of Hut 104 to a point beyond the fence and the tree-line. The date of the Great Escape was fixed to the night of 24/25 March 1944.[20]

The Great Escape

At 2040 hrs, the first men went down the tunnel. Johnny Marshal and Johnny Bull had to dig the last few inches to open the tunnel and to see the first escapees out. They had some difficulties loosening the top boards of the shaft, but in the end they managed. Johnny Bull has the first to put out his head from the tunnel. He was shocked. It was too short, and did not reach the edge woods encircling the camp as it had been planned. By contrast the exit was out in the open, and only fifteen feet from the nearest sentry tower. Following a brief discussion in the tunnel Bushell decided that the escape had to proceed.[21]

Hut 104 was full of men waiting to escape through the tunnel. Sqn Ldr David C. Torrens was sitting in a desk in the corridor calling each prisoner to the entrance of the tunnel as the escape progressed.[22] Torrens had a Danish link as well. He married a Danish woman, Tove Agnete Torrens (née Hald) in 1939. She served in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force.[23]

Christensen—who had been promoted to Flight Lieutenant on 27 February 1944—had partnered with the Australian Sqn Ldr James Catanach before the escape. Their plan was to escape to neutral Sweden. They managed to exit the tunnel unseen by the guards, and make their way to the Sagan railway station. They caught the express train to Berlin at 0315 hrs. reaching the capital shortly before 0730 hrs. the next morning. They spent the night in Berlin, and bought tickets for the train on 26 March to Flensburg. This city was located on the Baltic coast and close to the Danish border. They reached the city without incident, but ran out of luck. The were taken into police custody while walking along a pedestrian street, the Holm, in the inner city.[24]

Three days later, by orders from Berlin, Christensen and Catanach as well as the Norwegians Harald Espelid and Niels Fuglesang, who had also been arrested in Flensburg, were picked up by members of the Kiel Gestapo and executed. Their bodies were cremated in Kiel before being returned to Sagan. Several members of the Kiel Gestapo was sentenced to hang or prison after the war for their role in the execution of Christensen, Catanach, Espelid and Fuglesang.[25]

Christensen was Mentioned in Despatches on 8 June 1944 for his participation in the escape.[26] He was one of fifty prisoners shot by Gestapo following the escape. A total of seventy-six prisoners managed to escape. Only three succeeded: the Norwegians Jens Müller and Per Bergsland managed to get to Sweden, and the Dutch Bram van der Stok managed to escape to Spain.

Endnotes

[1] http://www.aucklandmuseum.com/war-memorial/online-cenotaph/record/C18990 (retrived on 23 February 2019).

[2] Parish registration, Randers parish. Born 8 October 1891, son of Svend Christian Christensen and Else Katrine Christensen (née Nielsen).

[3] Ancestry: New Zealand, Marriage Index, 1840-1937.

[4] Ancestry: New Zealand, Naturalisations, 1843-1981.

[5] Arnold Christensen - Wikipedia (retrieved on 23 February 2019).

[6] Franks, N. (2010). Dieppe: the greatest air battle.

[7] http://rcafsaskatoon.blogspot.com/2013_01_01_archive.html (accessed 23 February 2019).

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ancestry: New Zealand, World War II Appointments, Promotions, Transfers and Resignations, 1939-1945 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

[10] NANZ: 22775/3823/4, letter of 27 June 1942 from A.G. Christensen to his mother.

[11] Franks, 2010, op.cit.

[12] No. 26 Squadron RAF - Wikipedia (accessed on 23 February 2019).

[13] Leigh-Mallory, T. (2012). Air Operations at Dieppe: An After-Action Report. Canadian Military History, 12(4), p. 55.

[14] Veterans Affairs Canada (2005). The 1942 Dieppe raid, 4.

[15] Franks, op.cit.

[16] Veterans Affairs Canada, op.cit., p. 4.

[17] Franks, op.cit.

[18] Leigh-Mallory, T., op.cit., p. 8 and 16.

[19] Read, S. (2013). Human game: the true story of the ‘great escape’ murders and the hunt for the gestapo gunmen, p. 204.

[20] Brickhill, P. (2000). The great escape.

[21] Brickhill, P., & Norton, C. (1948). Escape to danger, pp. 289-292.

[22] Brickhill, P. (2000), op.cit., p. 168.

[23] Herning Folkeblad, 02.11.39.

[24] Read, op.cit., pp. 20-21.

[25] Read, op.cit., pp. 201-222.

[26] London Gazette issue 36544, 8 June 1944.