1st Off. Mogens Louis Bramson

(1895 - 1981)

Profile

Mogens Louis Bramson was a Danish born aero engineer, who served briefly in the RAF in 1939 and in the ATA in 1939-40. His main contribution to the air war, however, was as an independent consultant instrumental to the funding of the the development of the first British jet engine by Frank Whittle.

Mogens Louis Bramson was born in Copenhagen on 28 June 1895, to Louis Bramson and Karen Bramson (née Adler).[1] Karen Bramson was a well-known and internationally recognized author. She moved to Paris at the beginning of the First World War and lived there until her death in 1939.[2] Although living apart, the parents remained friends for life.[3] Louis Bramson, who was Jewish as his wife, was arrested on 1 October 1943 by the Nazis and sent to Theresienstadt. He was imprisoned in this camp from 4 October 1943 and until 15 April 1945.[4]

Bramson attended Metropolitanskolen in Copenhagen,[5] but was later transferred to Birkerød Statsskole to finish the Gymnasium.[6] He graduated in June/July 1913 from Birkerød Statsskole and continued studies as an engineer at the Polytechnic in Copenhagen.[7] He moved to England and seem to have completed his studies as engineer in this country. He became assistant to the Romanian professor and inventor George Constantinescu.

Bramson became a naturalised British subject in 1931 and was, thus, not Danish national when serving during the Second World War.[8]

Aero engineer and inventor

Bramson himself patented a number of inventions during his life, which did not only include inventions within the field of aviation. These include ball joints for pipelines (filed in 1918), flexible pipe line (filed in 1919), stop-valve for fluid-pressure systems (filed in 1920), and a spring, particularly for use in percussion-tools (filed in 1920).

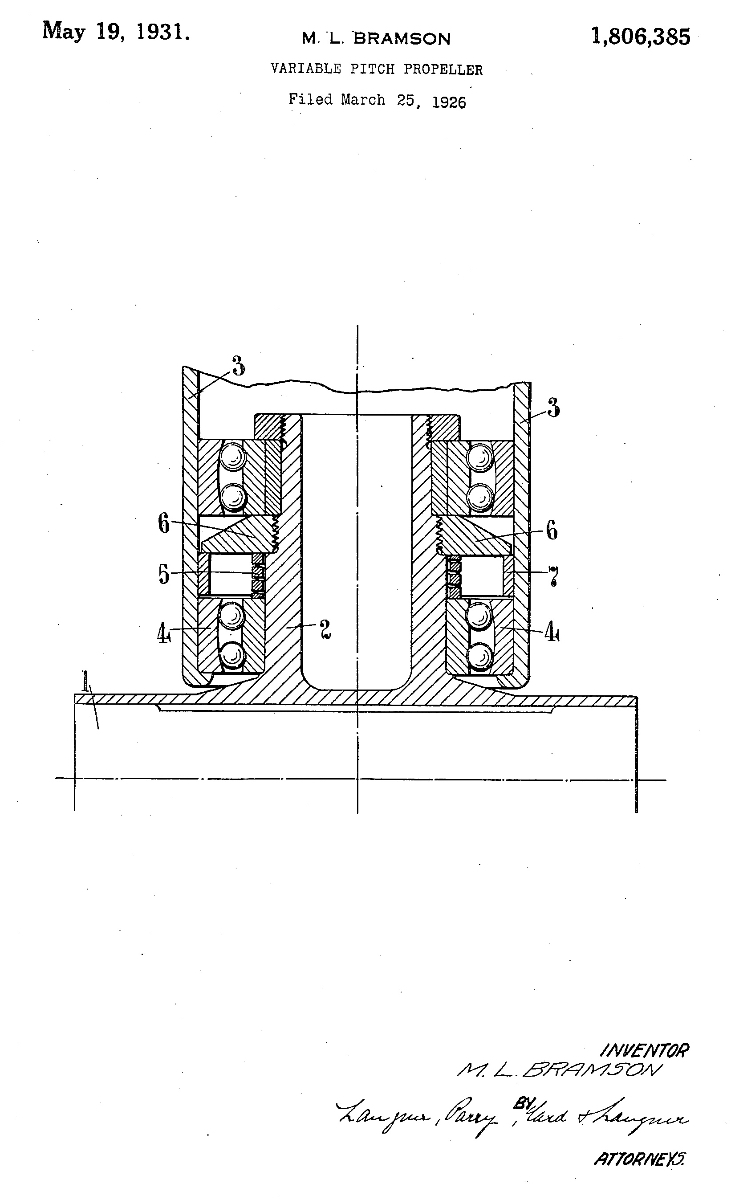

Within the field of aviation he patented a devise to the ‘control of aeroplanes and the like’ (filed in 1925), which would warn the pilot when an aircraft was about to stall, and a variable pitch propeller (filed in 1926).

Skywriting

Bramson was employed by Major J. C. Savage, a pioneer in skywriting[9], as the continental manager of his Savage Sky Writing Company Ltd in May 1923. He obtained his aviators’ certificate on 12 June 1923.[10]

He became the leader of the Scandinavian Sky-Writing Expedition in 1923-24. In July-August 1923, he performed his skywriting skills over in the air over the International Aero Exhibition in Gothenburg (ILUG - Internationella Luftfartsutställningen i Göteborg) flying in a RAF S.E.5a biplane named The Sweep (G-EBDU). He continued to Oslo in Norway followed by Stockholm, Sweden.[11]

He participated in the Kings Cup air race in July 1931 flying in Southern Martlet (G-ABBN). He had to retire at Shoreham and came 28nd.[12]

‘This must be done’

By 1935 Bramson had established himself as a a well-known independent aeronautical engineer and a consulting engineer. He was approached by Frank Whittle and the events that followed changed the course of the aero propulsion history.

In January 1930, Frank Whittle filed a patent for a gas turbine to propel an aircraft. At the time Whittle was Pilot Officer in the Royal Air Force and a flying instructor at the Central Flying School at Wittering. He had worked on his ideas of the gas turbine for some years, but had not been able to get support for further development neither from the Air Ministry, nor the industry. Whittle received distinction when attending the Officers School of Engineering at RAF Henlow in 1932 and was permitted to take a two-year engineering course at Peterhouse College in Cambridge. However, while succeeding academically, Whittle lacked the funds for the further development of his ideas. He could not even afford the renewal fee for his patent when it became due in January 1935.[13]

Whittle partnered with two ex-RAF servicemen—(later Sir) Rolf Dudley Williams and James Collingwood Burdett Tinling—who worked on his behalf to gather public financing for the development. Whittle was introduced to Bramson through Tinling’s father. Skeptical at first, Bramson agreed to study Whittle’s proposal.[14] He later recalled

At the end of that period I got quite excited. First because of the insight, clarity and accuracy of his presentation and calculations; secondly because my scepticism of any project based on internal combustion turbines (which had hitherto resisted all practical development efforts) disappeared when I realized that here, for the first time, was an application where maximum energy was needed in the turbine exhaust, instead of in the shaft. This was, of course, the reverse of all past objectives for such turbines. And, thirdly, because of the dramatic advance in aviation technology implicit in Whittle's theories. I suddenly felt "This must be done!", (which meant "financed").[15]

Branson introduced Whittle and his partners to the investment bank O.T. Falk & Partners, who again asked Bramson to act as their consultant on the project.[16] They wanted a independent view on the feasibility of the concept.

Bramson finished his Report on the Whittle System of Aircraft Propulsion (Theoretical Stage) in October 1935,[17] and it was on the basis of this report that the development of the jet engine was originally financed and organized. In January 1936, the parties agreed to establish Power Jets Ltd. The directors were L. L. Whyte and Sir Maurice Bonham Carter. Bramson acted as alternate director for Sir Maurice as well as official consultant.[18]

On April 12, 1937, the first runs of an experimental turbojet, called the W.U., were made. Whittle worked on several engines following the W.U. leading to the W.1 engine used for the flight-test of the single-engined Gloster E.28/39 on 15 May 1941. The development of the engine culminated in the advanced

W.2/700 rated at 2,500 lbs thrust.

Bramson’s report, support and consultancy was instrumental in making that happen

Service Pilot

Bramson was granted a commission as Pilot Officer on probation in the Administrative and Special Duties Branch for the duration of hostilities on 19 September 1939.[19]

Two weeks later, on 2 October 1939, he was attached to the Air Transport Auxiliary remaining in service as pilot for five months until 6 March 1940. He held the rank of First Officer and was stationed at the 1 Ferry Pilot Pool at White Waltham.[20]

Bramson bought one of the first privately owned Spitfires after the war. The Spitfire IIa (converted to V) P8727 had originally built at Castle Bromwich in 1941 payed for by funds raised from Dutch citizens in the Dutch East Indies and named Den Pesar. It had seen action with 276 Sqn (AQ-O) in 1943-44. It was bought by Bramson on 16 July 1946, converted to civilian aircraft and issued a certificate of airworthiness on 22 October 1946. Bramson used the aircraft—now G-AHZI Josephine—to commute between Exeter and London on business.[21]

In April 1947 he flew the aircraft to Copenhagen, Denmark. As he took off from Copenhagen-Kastrup airport on 15 April 1947 the engine cut. He failed to return to the airport and had to crash land in a field near the airport. He was unharmed, but the aircraft was written off.[22]

A Membrane Lung for Open Heart Surgery

Bramson settled permanently in the United States in 1953.[23] He met the American surgeon Dr. Frank Leven Albert Gerbode, a pioneer in cardiovascular surgery, who got him interested in Biomedical engineering. Bramson became the first non-medical doctor to work as an investigator for the American Heart Association. Over the next years, Bramson worked with Gerbone and Dr. John Jay Osborn for the American Heart Association on a Membrane Oxygenator.

Bram very quickly mastered all the mathematics and physiological principles of dealing with blood and circulation and, being a very brilliant man, he quickly saw the problems and began to try to solve them.[24]

The work resulted in the Osborn-Bramson-Gerbode Rotating Disc Oxygenator, which was used for open heart surgery[25] and later, after after six years of development they were able to present a membrane lung, the Bramson Membrane Oxygenator, in 1965.[26]

Branson lived in the United States for the rest of his life. He was naturalised as a US Citizen in 1959,[27] and died in San Francisco on 26 February 1981.[28]

Endnotes

[1] DNA: 1911 Census of Denmark.

[2] Fabricius, Susanne: Karen Bramson in Dansk Biografisk Leksikon,at lex.dk. Retrieved from https://biografiskleksikon.lex.dk/Karen_Bramson (15 July 2022).

[3] Karen Bramson (1875-1936), Dansk Kvindebiografisk Leksikon. Retrieved from https://www.kvinfo.dk/side/597/bio/216/origin/170/ (15 July 2022).

[4] FHM: 46-10862-244.

[5] Bravo, Mr. Bramsom, Politiken, 25 June 1975, Section 2, p. 1.

[6] III. Forelæsninger, Øvelser og Eksaminer. (1913). Københavns Universitets Årbog, 1, https://tidsskrift.dk/kuaarbog/article/view/84303 (accessed on 15 July 2022).

[7] IV. Forelæsninger, Øvelser og Eksaminer. (1914). Københavns Universitets Årbog, 1, https://tidsskrift.dk/kuaarbog/article/view/84013 (accessed on 15 July 2022).

[8] The London Gazette, 33733, 7 July 1931, p. 4432.

[9] Skywriting is the process of using one or more small aircraft, able to expel special smoke during flight, to fly in certain patterns that create writing readable from the ground, cf. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skywriting

[10] Ancestry: Great Britain, Royal Aero Club Aviators’ Certificates, 1910-1950.

[11] Mulder, Rob J.M. (2011). Skywriting - Mr. Bramson above Christiania (Oslo). Retrieved from https://www.europeanairlines.no/skywriting-mr-bramson-above-christiania/ (15 July 2022).

[11] King’s Cup Race 1931, A Fleeting Peace. Retrieved from http://www.afleetingpeace.org/index.php/pioneering-women/kings-cup-1931 (16 July 2022).

[13] The First Patent, Sir Frank Whittle. Retrieved from https://frankwhittle.co.uk/the-first-patent/ (16 July 2022).

[14] Meher-Homji, C. B. (2002). Enabling the Turbojet Revolution - The Bramson Report. Global gas turbine news, 42(1), 16-20.

[15] Kardos, G. (1971). This Must be Done ! (A).

[16] Golley, J. (2010). Jet: Frank Whittle and the invention of the Jet Engine.

[17] Bramson, M. (1970). Report on the Whittle System of Aircraft Propulsion (Theoretical Stage)—October 1935. The Aeronautical Journal (1968), 74(710), 128-133.

[18] Golley, J. (2010). Op.cit.

[19] The London Gazette, 34694, 25 September 1939, p 6505.

[20] ATA Personnel Database, Air Transport Auxiliary Museum & Archive at Maidenhead Heritage Centre.

[21] Mogens Bramson: From Skywriting to Biomedical Engineering, IMS News, III(1), 1974, p. 1 and 4.

[22] Spitfire nødlandet paa Amager, Horsens Avis, 16. april 1947, p. 1.

[23] Ancestry: California, U.S., Federal Naturalization Records, 1843-1999.

[24] Gerbode, F. (1985). Frank Leven Albert Gerbode : pioneer cardiovascular surgeon.

[25] Osborn, J. J., Bramson, M. L., & Gerbode, F. (1960). A rotating disc blood oxygenator and integral heat exchanger of improved inherent efficiency. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 39(4), 427-437.

[26] Bramson, M. Et al. (1965). A new disposable membrane oxygenator with integral heat exchange. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery, 50, 391-400.

[27] Ancestry: U.S., Index to Alien Case Files,1944-2003.

[28] Ancestry: California, Death Index, 1940-1997.